You can support my writing via a one-off or monthly tip on Ko-Fi. If you don’t like my writing, consider it a tip for my landlord. Landlords are having a very hard time at the moment.

This week I watched all of ITV’s Broadchurch (2013-2017). It’s for work. I’m in development on a sitcom that uses elements of the police procedural format, so I needed to closely analyse the plot structure. I also needed to closely analyse how beautiful David Tennant is – which is very, a lot, and very.

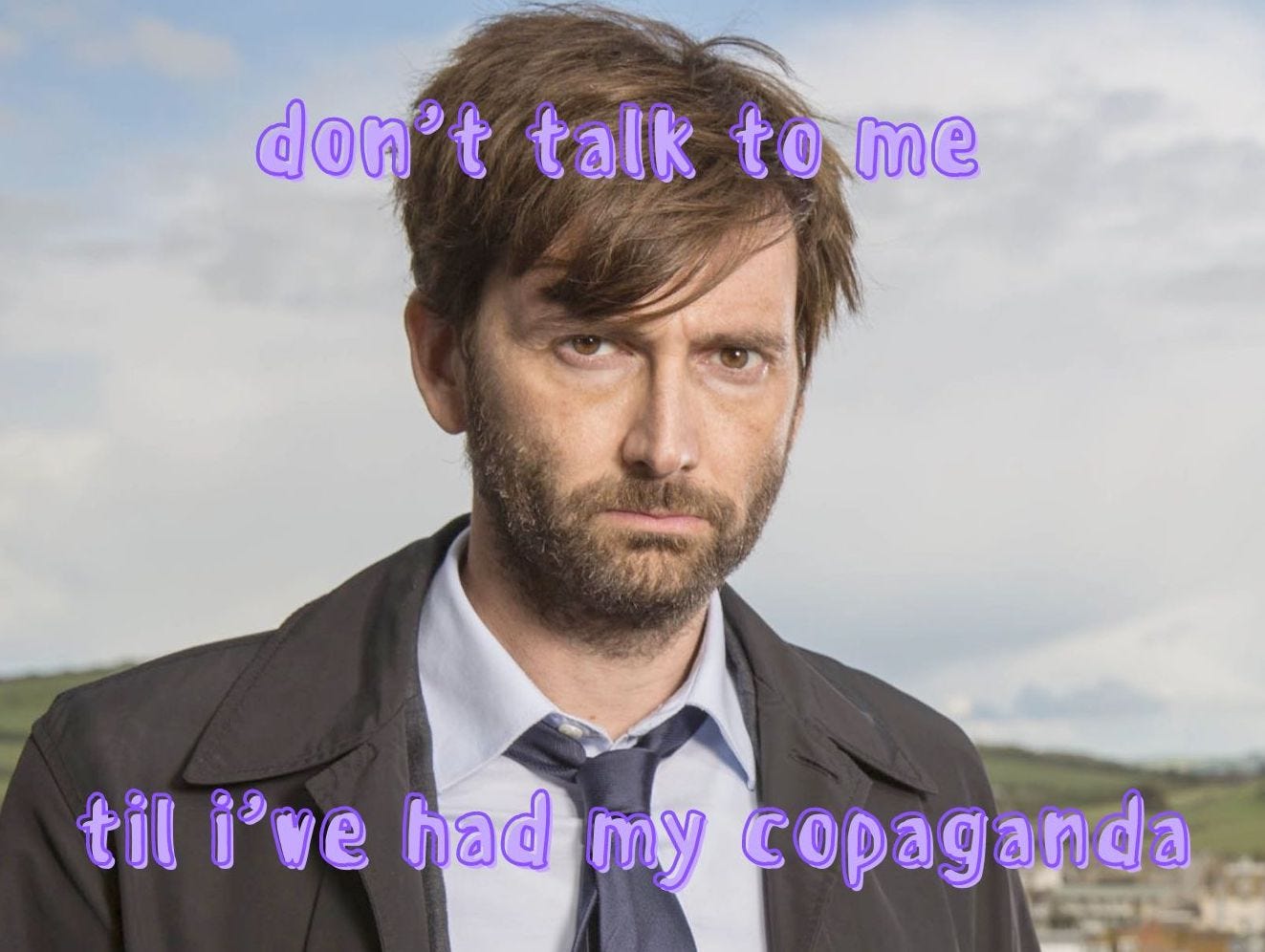

Politically, I feel conflicted about my love for shows that valorise the police. So why am I so obsessed with them?

I’ve always found police procedurals weirdly comforting. My dad got me into The X-Files when I was much too young, and then the Hannibal Lecter films when I was still much too young. By age 11, I knew I wanted to be a brilliant but troubled FBI agent. Well, either that or a cannibal.

I suspect my affection for long-running American police procedurals – like NCIS, The X-Files and CSI – is driven by the same thing which first got me into sitcoms: I am fascinated by the repetitive precision of the writing.

After all, schedule-stuffing American police procedurals have the same structure as sitcoms. There may be a loose series arc, but every episode is also a self-contained story which must be understandable to someone who has never seen the show before. And whatever this week’s problem, the plot must always reset at the end of the episode, plonking our characters back where they started, ready for next week. The predictability is relaxing. A gunshot to the head is the rock of the cradle. Purgatory is the aspiration. Curb Your Enthusiasm shares as much DNA with NCIS as it does with Seinfeld.

Larry David is an asshole. Women are murdered. I feel comforted.

Carmen Maria Machado’s story Especially Heinous: 272 Views of Law & Order: SVU (in the anthology Her Body & Other Parties, 2017) brilliantly lances this flattening of violence into cosy weekly narratives. Especially Heinous takes the form of episode descriptions for the eponymous procedural. For example:

“REDEMPTION”: Benson accidentally catches a rapist when she Google-stalks her newest OkCupid date. She can’t decide whether or not to mark this in the “success” (“caught rapist”) or “failure” (“date didn’t work out”) column. She marks it in both.

In the same vein, Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell once said of their gruesomely realistic Jack the Ripper documentary-comic From Hell (1989-1998):

We don’t want to turn murder into a parlour game.

Their accusation is that this is what everything from Agatha Christie to CSI is doing. In most cop shows and films, murder is not portrayed as a crime against a human being. It’s stylised and clean. Many recent police shows (including, to some extent, Broadchurch) are a reaction against that: they are gritty and realistic and everyone has sexy eye bags.

The realism can be shocking. I really had to work up to watching series 3 of Broadchurch because it was about a serious sexual assault, in contrast to series 1 and 2, which were about the fun crime of child murder.

I’m joking, but I’m also right. Sex crimes ARE less fun, because murder in a police procedural is usually a cartoonish crime at the centre of a puzzle box. We never hear about the suffering of the victim, because they are deliberately absent from the narrative.

Even putting aside their sinister cosiness, I want to hate these shows. There’s a tendency in popular culture to produce “copaganda” – works that uncritically make heroes of the police whilst ignoring the institutional violence, racism and misogyny at the heart of their organization. The problem is, most fictional storytelling is going to lean towards showing how the protagonist is an interesting individual actor, rather than the product of their institution. As viewers, we like to see a complex character making tough choices. This is why many fictional cops don’t “play by the book”, and act as if they are outside police infrastructure. These shows necessarily make individual police officers into radical – if troubled – heroes, detached from the violent power structures in which they exist.

They also tend to play into authoritarian tropes. Vertiginously silly James Spader vehicle The Blacklist (2013-2022) justifies torture in every single episode, which, without exception, goes like this:

1. A cute little American girl with pigtails is in danger.

2. Time to torture a foreigner!

However, I must recommend the show, because it features a scene where the writers demonstrate James Spader’s character is classy by showing him – I am genuinely not making this up – in a fedora shop. I’ve watched 20 hours of it already.

(The trailer contains almost the entire first episode and is one of the most unintentionally funny things I’ve ever seen.)

As a genre, the police procedural is the ultimate neoliberal art form: it critiques the old institutions of power as slow-moving and corrupt, whilst valorising the strong individual who stands up to fusty red tape and gets the job done. This is police-officer-as-entrepreneur. And like any good neoliberal, the officer’s apparently radical deconstruction of the old institution only reasserts the power relations that underpin it even more: the monolithic police force will always be corrupt, but that’s okay because brave individuals will can overcome them, so long as they are permitted individual liberty.

This isn’t intended as a big critique of Broadchurch, by the way, which I really enjoyed (at least, the fun bits about killing kids). I think Broadchurch is generally pretty deft with its use of these tropes. What Broadchurch actually got me thinking about was how the appeal of these shows has changed for people of my age. I think it’s still cosy murder. But I think shows like Broadchurch now also speak to another issue: our abusive relationship with work.

Police procedurals tend to be about the officer who cannot have a personal life because his work consumes him. Broadchurch S1 is essentially the story of a cold rationalist man – Hardy (David Tennant) – teaching an emotional, homely woman – Miller (Olivia Colman) – that she cannot let her private life have primacy over her work, because work and duty to the work is the only true stabilizing force in life. It is the only thing you can trust. And indeed, SPOILERS, it’s her husband who dunnit, trust nobody.

These Workaholic Cop narratives take on new significance for precariously employed Millennials and Gen Z. They offer a comforting fantasy in which your hard work – even if it is not recognised by your jumped up superiors on the force – offers dignity, stability and the satisfaction of a job well done. Your all-consuming, unstable career might not pay your bills, but at least you caught the murderer. And got some sexy eye bags along the way.

Then again, maybe I just liked this show because it’s nice to look at David Tennant. Maybe I didn’t really need to watch all of Broadchurch, because it’s not even the right type of trashy American, monster-of-the-week procedural to be useful for my research.

Once I finished Broadchurch, I made my boyfriend watch a biopic of RD Laing, also starring David Tennant. I’m always going on about RD Laing so he didn’t suspect a thing. He thought I was just watching it because it related to one of my interests. Now David Tennant just needs to do make 10-part series about 1970s cybernetics, or not folding the laundry, and I’m sorted.

Thanks for reading HIGH RESOLUTION GORE & GRAPHIC VIOLENCE, a newsletter by UK-based writer Zoë Tomalin. If you enjoyed this edition, please share it on social media, ask a friend to subscribe, or drop a tip here.

Read about how I learned to be assertive on Baldur’s Gate 3 here: